Charles Stewart Parker was born in 1879 in Corinne, Utah Territory, a non-Mormon transportation hub in the northern part of the state near present-day Logan, Utah. He was born to John Byron Parker (watch for a future blog post about John Byron) and his wife Odella Parker nee De Reyno. John Byron worked in Corinne as a barber where he cut hair for travelers who stopped over in the town.

Railroad companies skipped over Corinne when they rerouted which quickly turned it from a boom town into a ghost town, as was common in the American West. The Parker family picked up and moved to another boom town, Eureka, Nevada, in search of new clientele for John Byron’s barber business. According to the census, Charles gained two siblings while living in Nevada, one in 1881, and another in 1883. The family had both Black and white ancestry and they were often characterized by census takers as “Mulatto.”

In 1883, when Charles was six years old, the family of five moved to Spokane, Washington. He attended public schools where he was a standout athlete in track and football. He graduated from Spokane High School as part of the class of 1898. After graduation, Charles headed to Washington D.C. where he attended classes at King Hall seminary, a theological training school associated with Howard University. He fell in love with Annice Marguerite Lewis and they married in D.C. The newlyweds returned to Spokane in 1901 before Charles could finish school due to health issues.

Once back in Spokane, the couple moved into the family home at 2826 West Dean Avenue and Charles found work as a shipping clerk at the Crane Shoe Company. Beyond work, he became an active member of Spokane’s Black community. He was a leader of a congregation, the St. Thomas Episcopal Mission, where he would often read sermons and participate in ceremonies. In 1908, Charles and fellow Black leaders began planning for the centennial celebration of President Abraham Lincoln’s 100th Birthday and he was appointed secretary of the Lincoln Centennial Association. In 1909 Charles co-founded the Nonpartisan Colored Improvement Club, which is likely the first non-religious and non-partisan organization in Spokane dedicated to advocating for the rights of Black Spokanites.

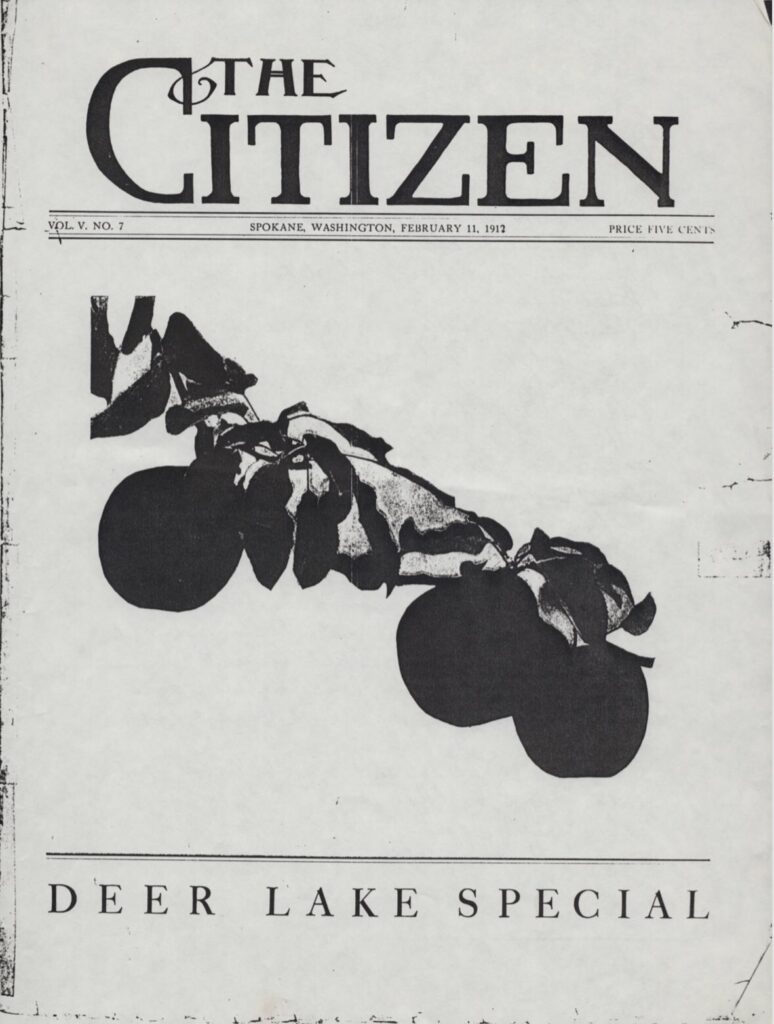

In 1908 Charles partnered with another Charles, Charles Barrow, the son of Spokane pioneer and former slave Peter B. Barrow Sr., to found Spokane’s first Black-owned newspaper, The Citizen. Charles Parker served as the paper’s editor from 1908 to 1913 when the paper ceased printing. After the newspaper, Charles continued to work at X-Ray printing, a Black-owned print shop, while also pursuing agricultural education at Washington State College in Pullman, WA. Parker’s interest in agriculture and botany was almost certainly spurred by his involvement with the Deer Lake Irrigated Orchard Company, a Black-owned fruit orchard located north of Spokane. Parker was a co-owner and treasurer of the company.

In June of 1917, just two months after the United States entered World War I and one month before Spokane conducted its first draft lottery, Charles enrolled in the United States Army (joining his brother who had served in the United States Navy for over a decade). Charles was sent to Fort Des Moines in Iowa to attend officer training specifically for Black candidates. In October of 1917 he received an officer’s commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 366th Infantry Regiment and was quickly promoted to 1st Lieutenant. In June of 1918, the 366th departed for France where they were active in combat at Alsace and at Meuse-Argonne, the principal offensive for U.S. forces in France. Charles led his platoon to the frontlines under heavy fire and through thick fog of noxious gasses. In a letter from the front to a friend back in Spokane, 1Lt Parker remarked that “the question as to whether the American negro will stand the pressure of trench warfare is no longer a problem. He has been called to the bat and hit a home run the first inning.” Parker and his troops advanced into Germany where they remained until the Armistice was signed.

1Lt Parker returned to Spokane in May of 1919 where he was greeted with a celebration from his friends, family, and the local NAACP chapter. Soon after he returned, the Department of War awarded him with the rank of Captain for his heroic leadership on the Western Front.

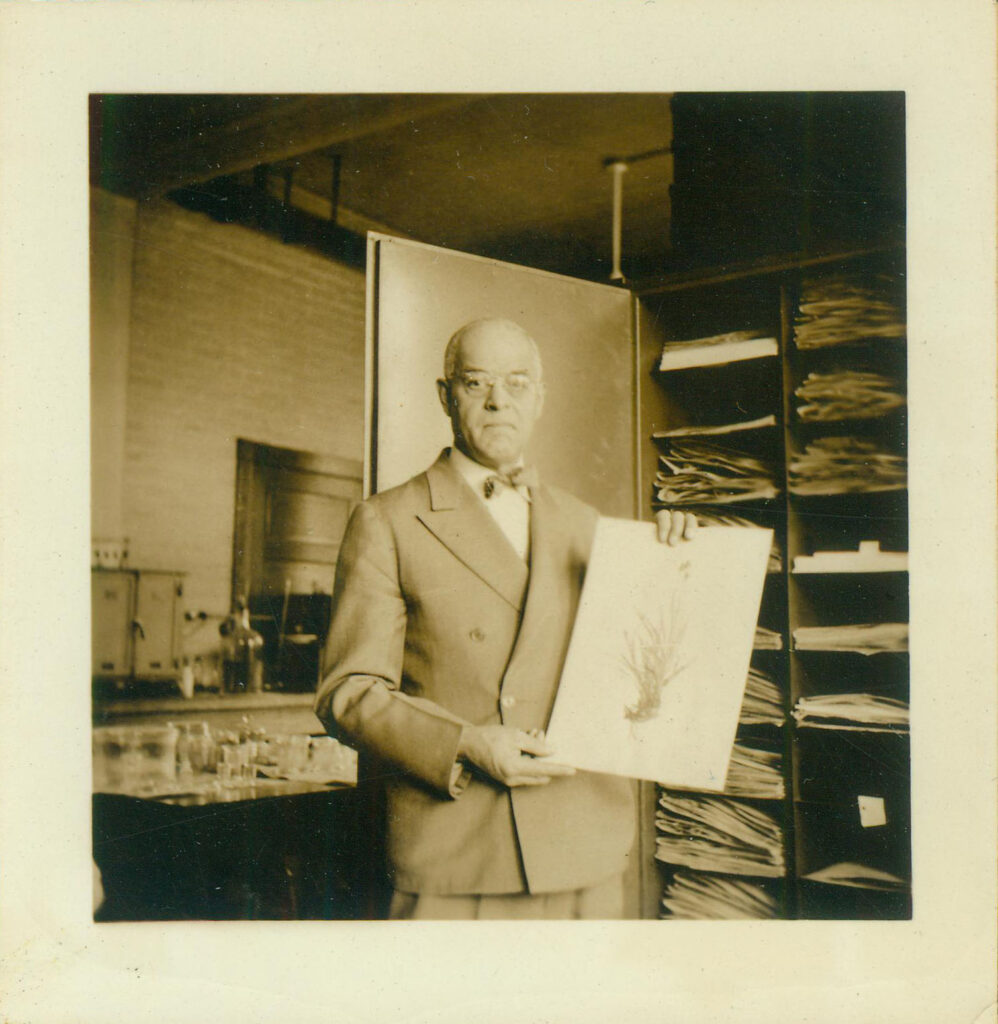

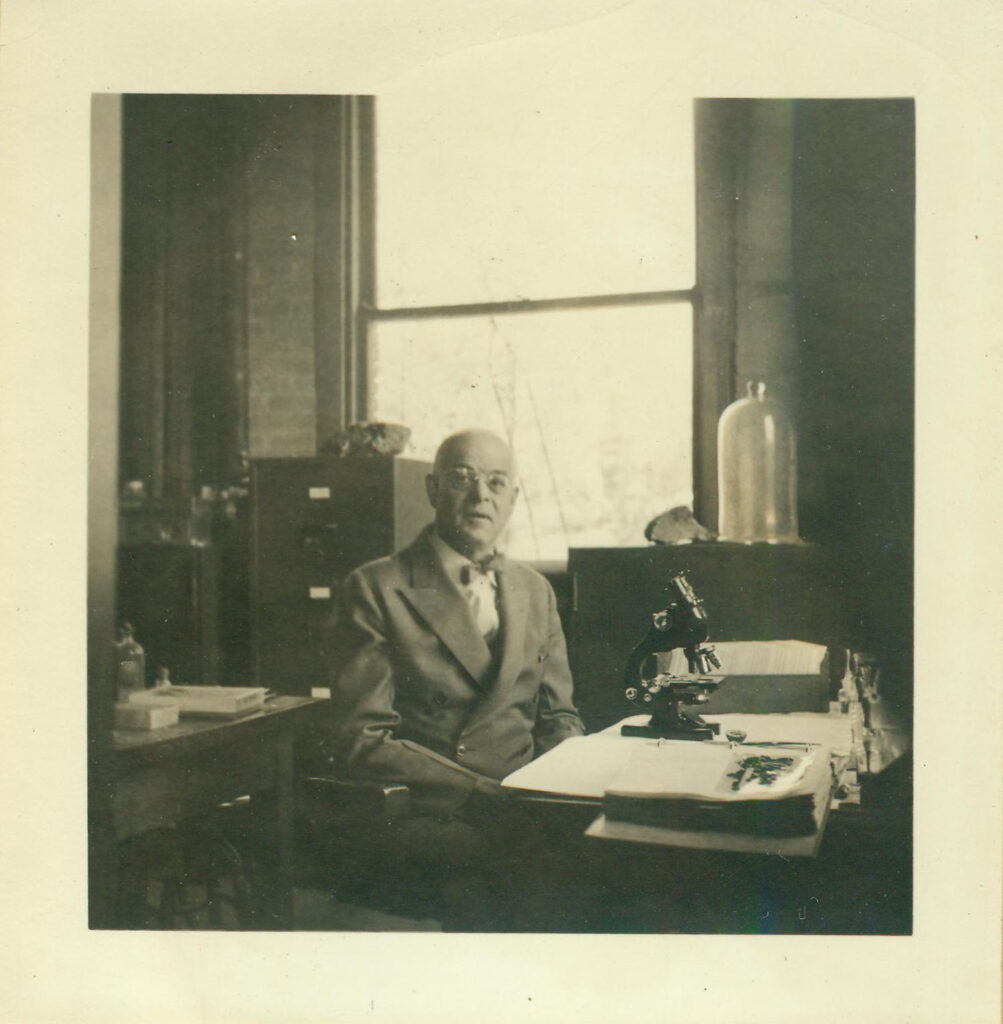

In 1919, Charles was awarded a professor position at the Tuskegee Institute, a university for Black Americans in Alabama founded by Booker T. Washington. While teaching, he continued to pursue his own education culminating in a doctorate degree in plant pathology from Penn State University in 1932. After graduation, he was hired as a professor at Howard University, a famous Historically Black College and University known by some alumni as “the Mecca,” where he was Chair of the Department of Botany for sixteen years. The Charles S. Parker Herbarium on Howard’s campus, a collection of specimens he assembled, is named in his recognition.

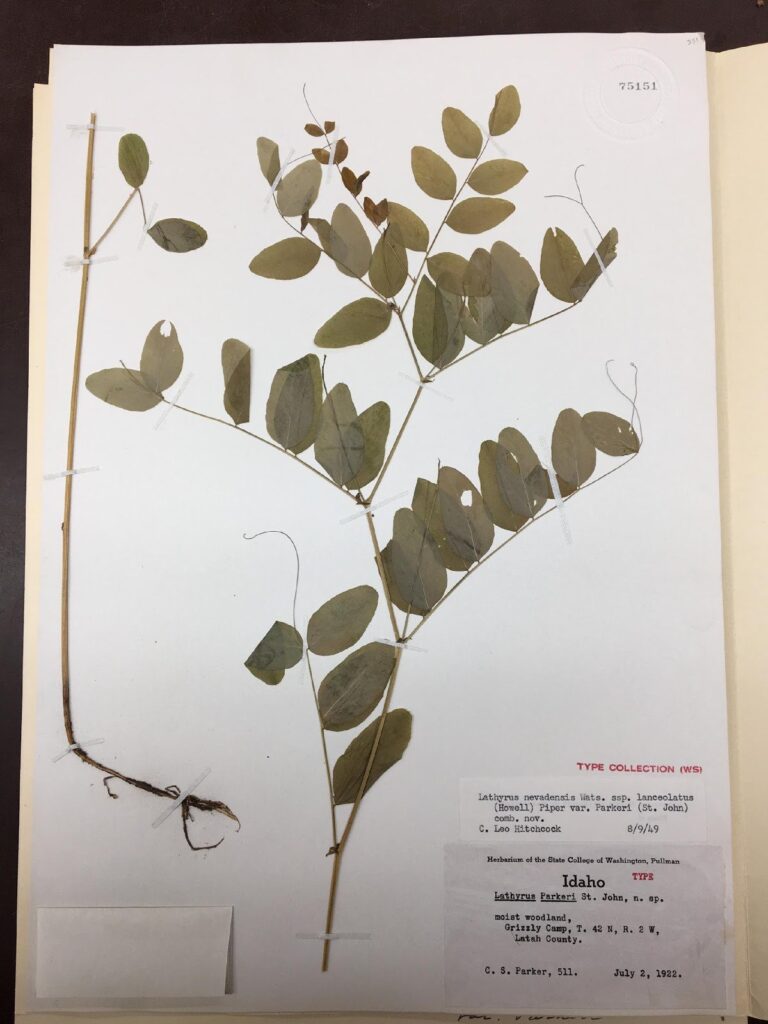

During his academic career, Charles returned home to the Pacific Northwest in search of distinct flora native to the region. He collected thousands of specimens which he documented in two journal publications. Some of the specimens he collected are still held at Washington State University’s Marion Ownbey Herbarium. Charles’ contributions to the field of botany were recognized by renowned botanist Harold St. John when he named a species of pea plant after him (Lathyrus parkeri St.John).

Charles Parker was a product of Spokane’s public schools. He was an influential community leader and he served his country selflessly in World War I. He became an accomplished botanist and left a lasting legacy at Howard University. In 1950, at 71 years old, Charles passed away in Seattle, Washington.